It all started with LOGO. If you don’t remember making this little turtle crawl around and draw stuff, then your childhood wasn’t complete. In fact, you should probably go back and do it now.

Seymour Papert, a researcher at MIT, reasoned that children could learn programming more easily if they were given a fun programming environment to play around in. This was so successful in the case studies he observed that he was forced to develop an explanation. He called his theory of learning ‘constructionism’ (because the student can construct their own knowledge by experiment). This spawned a genre of software toys designed to teach programming (all after my time, unfortunately). Toys like Alice, Greenfoot, RoboMind, GameStar Mechanic (my favorite), and Scratch (the most popular). Even Lego’s robotics platform, Lego Mindstorms is an extension of the ideas Papert outlines in his books ‘Mindstorms‘ and ‘The Children’s Machine‘ and is perhaps the most faithful to them.

These efforts have engaged millions of students in learning about technology, and has given them great early exposure to the field. In my own first grade class, we had a teacher (I think his name was Mr. Costa) who took care of the computer lab and taught computer class. We were taught the basics of LOGO, and then asked to produce a project of our choosing. My partner and I worked diligently to put together an animated scene of an F1 racetrack, complete with cheering fans and cars circling the track.

We were very proud to present what we’d done to the class, but when the time came we found out that we were the only group out of 10 or 12 who had actually done anything substantial. A few pointy spirals. A few rounded spirographs. Disappointing. The next year Mr. Costa was replaced, and our ‘computer class’ was about typing and learning to use Microsoft Word.

Maybe I was just the right kind of kid to get hooked on programming early, but for most of the first-graders in my class, the motivation just wasn’t there. That’s what I see as a lack inherent in these toys built with constructionism in mind: motivation. Why am I exploring this educational environment? What am I supposed to do here? When some students are told “you can do anything,” what they hear is “there’s nothing to do.”

In my case, I was motivated by curiosity. For many people, motivation is more extrinsic. Code.org lists resources for motivated adults to learn how to code, usually for career-oriented reasons. Kids in the third world, and everyone in the eighties, when Papert was doing his work, are at least somewhat motivated by the novelty of interacting with the machine itself.

Today, getting to interact with a computer is not such a treat. For many school-age children in the US, it’s the default state of being. The software has to have a better ‘why’ built into it. That’s where games come in.

Many authors have written (more eloquently than I ever could) why games are such a perfect learning environment. Central to those arguments is the concept of intrinsic motivation. Winning a game is gratifying for its own sake (there’s evolutionary hard-wiring there). Games, ideally, keep players always at the edge of their capabilities, wanting to get better to accomplish the next task and unlock the next bit of power-up or narrative or whatever digital carrots the game designer decides to add. Games also offer a kind of social capital that creative tools cannot; creative work cannot be compared quantitatively in the way that a score or level can.

Until recently, there haven’t been many efforts to create an actual Game that teaches programming. Let’s go over a few.

This is going to stand in for a whole bunch of what are essentially puzzle games, like Daisy the Dinosaur and Robozzle. I’ve got nothing against puzzle games, and I think any game that adequately introduces the mechanics of programming has to have a puzzle component. That said, puzzle games are the genre of game most like homework. These games in particular don’t introduce any kind of stakes – no reason to complete the puzzles. Also, one of the principles of responsive games is to decrease, as much as possible, the (user input)/(in game consequences) ratio. By their nature, these kinds of puzzles require a lot of player input for very little onscreen action.

I titled this section after Light Bot because it’s actually the best I’ve seen in this category, but most entries in the category are characterized by very little professionalism. It’s easy to speculate on the creator’s thought process. “I’ve never made a game before, but I’m a programmer, so how hard could it be to make a game about programming?”

Code Hero (unfinished)

There’s been a lot of hubbub about Code Hero recently, but the concept is still an exciting one. It uses the concept of the action-puzzle game, popularized by games like Portal and Quantum Conundrum. It also gives the player a first-person perspective, so they can feel situated in this world where code is so important. It reminds me of something Papert says in ‘The Children’s Machine’: “What would happen if children who can’t do math grew up in Mathland, a place that is to math what France is to French?” In Code Hero, you grow up in Codeland. I am anxious for the Primer Labs team to continue development.

The one criticism I have is that this game (and Portal) feel a bit contrived. I’m in some kind of laboratory environment where I have to complete spatial reasoning puzzles…because…things? In Portal they call it like it is — “tests.” A robot is testing you, to see how clever you are. That narrative conceit (which was always a cop-out) can only be used once.

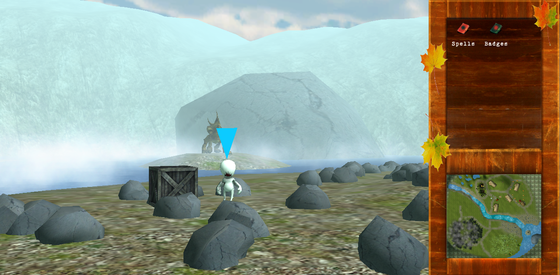

Code Spells (unfinished)

Code Spells has all the situated-learning benefits of Code Hero, but also addresses my criticisms by placing the player in a fantasy world where she must help little gnomes to complete tasks. Meanwhile, there is a monster roaming around. The idea of code-as-magic is one that I love. It explains why magic is so often botched and broken, why it takes a lot of concentration and diligence, and why it is best practiced by ancient masters.

All my criticisms of this game are a consequence of it simply not being finished. I can’t wait to see what the team at ThoughtStem adds next.

Codemancer (unfinished)

I independently decided to use the magical-programming metaphor for a game I’m developing called ‘Codemancer’ which I’m not ready to talk about in detail, but which I hope will be an example of how to do this genre right. The main difference in my game is that it has a less specific focus. I thought it would be better to develop my own visual programming language (which has a lot in common with LOGO), so I could make the basics as accessible as possible. I hope you’ll follow along in its development by following me on twitter here.

I’m not proposing that constructionist learning environments be eliminated. Whether a student responds to an exploratory style depends on the individual student, and indeed many students respond well. There are, I believe, a lot of learners who are underserved by making exploration the only means of discovery. I’m excited for the time, approaching soon, when these learners will have the option of a more narrative, guided, fun-motivated way to learn programming.

PS – If you have a game about programming you’d like to see mentioned, please add it as a comment to this post and I’ll try to play it and add my thoughts.