The Kickstarter for Codemancer was successfully funded at the end of May, and I learned a lot in the process. I’d like to share as much of that as I can.

First of all, let’s look at the high-level results. The final amount raised was $52,725 by 1,862 backers. That’s 439% of the original goal. I couldn’t be more thrilled, or more grateful to my amazing backers. But enough gratitude. You came here for details, and details you shall have!

A lot of factors seemed to contribute to the success of the campaign, so far as I can tell. Let’s go through some.

The Research

I did not embark on my Kickstarter journey lightly, but sought the advice of many experienced people. For instance, I attended the IGDA ‘Kickstarting Your Dream Game’ panel, which brought together many Kickstarter campaign creators to share their experiences and advice. I sought one-on-one advice from everyone I knew who had prior experience to offer, including Kee-Won Hong (of Iterative Games), Max Temkin (of Cards Against Humanity), Ryan Weimeyer (of The Men Who Wear Many Hats), all of the Young Horses, Craig Stern (of Sinister Design), and many more.

I also kept a close eye on other crowdfunding campaigns both successful and unsuccessful, especially ones in the categories of games, education, and educational games. I didn’t make any systematic observations, but by immersion I hope to gain an intuitive feel for what others had done well or poorly in the past. This was useful, but I still wouldn’t call myself an expert.

The Video

The video is the first thing people see about a campaign (other than the name), and I wanted mine to be good. It would be especially embarrassing to have a bad video considering that I spent 4 years at (very expensive) NYU film school. I watched a lot of Kickstarter videos in order to figure out what was done well or poorly by others.

At first, I wanted to make a pure trailer for the game, inspired by Hyper Light Drifter’s amazing Kickstarter video (and I’m sure you’ll still see some resemblance), but I was convinced by a friend to make the video say more about the impact that the game is intended to have. I believe that this was a fantastic decision, despite my misgivings about relying too much on making the game into a ’cause.’ The game has a couple of messages which I’m really proud of, but I think are more effective if discovered by the player rather than said. Unfortunately, crowdfunding eliminates the luxury of discovery. The positive messages I tried to communicate through the video were

- Programming is a worthwhile thing to teach children, especially girls.

- Games are a great way of teaching things.

- This game project in particular combines the previous two ideas in an effective and fun way.

An additional message, which is sort of implicit, but isn’t really clear except after doing some research, is that myself and my team are capable of delivering such a game. Some feedback I got indicated that even people who believed int he mission of Codemancer couldn’t bring themselves to contribute to any Kickstarter project because of bad experiences in the past, and I could have given them some assurances of my competence in the video (although honestly this is my least favorite part of many Kickstarter videos — “I’m a veteran of blah blah”).

What you watch above is actually the second version posted. In the first version of the video, I didn’t talk over the gameplay or playtesting footage at all, but I swapped it out with a voiceover version a few days into the campaign because I got a lot of feedback that the video was too long. It seems like 2:30-3:00 is really a sweet spot (the length of a typical pop song – coincidence?) and the first version was a little over 3:30.

Building an Audience Pre-Kickstarter

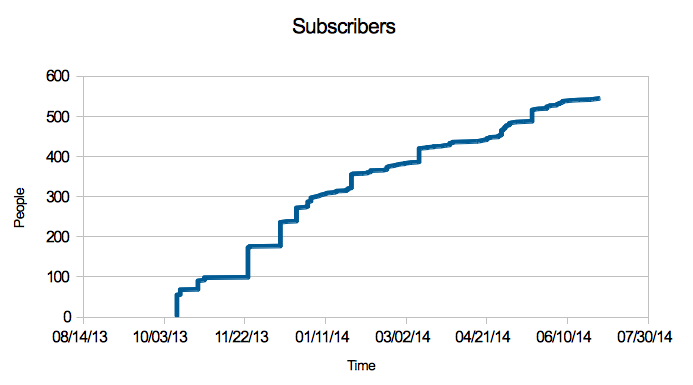

A few months into Codemancer development, I put up a placeholder page on LaunchRock, just to have a place to direct interested people, and a way of collecting their information. Eventually, I transitioned to a MailChimp list, as I began to send out development updates. That list grew steadily over the period from October 2013 to today (you can still join, here).

The stepwise look of the chart is because every time I’d go to an event or a conference I’d ask if people there would be willing to join my mailing list. Then, when I got home, I’d enter all the email addresses at once.

I also tried to build up my follower count on Twitter before the campaign launched, which others have figured out how to do far better than I. One thing that helped is that I blog regularly on Gamasutra. Once I started to develop Codemancer, I also started including a link to my twitter account at the top or bottom of my blog posts. When I launched the campaign I had about 950 twitter followers on my personal account, and just 20 or so on the Important Little Games company account.

Sending out an email to my mailing list, and tweeting as soon as the project went up really helped with the next contributing factor…

Funded Early

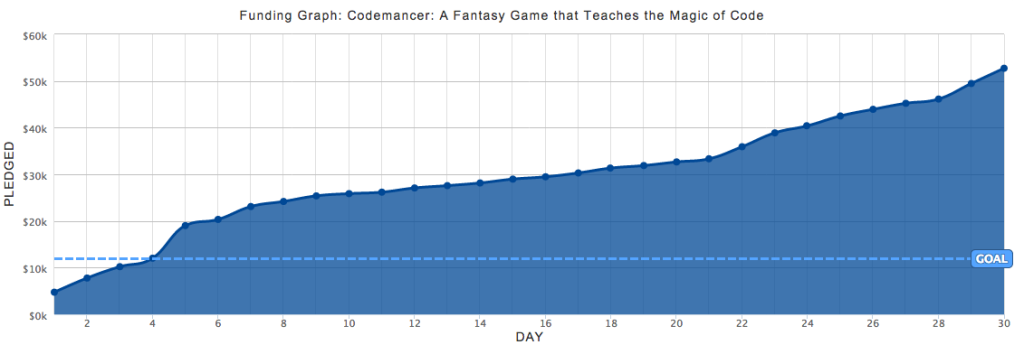

I was advised that many Kickstarter backers prefer to contribute to successfully funded projects, or projects which are projected to be fully funded. For this reason, and because I knew I’d continue to work on Codemancer regardless of the outcome of the Kickstarter, I lowered my goal from the original $20,000 I estimated I’d need to the more modest $12,000. In retrospect this was a good decision.

Here’s the full funding history of the project, courtesy of KickSpy:

As you can see, the project was funded on day 4 (actually, just an hour before we hit day 5).

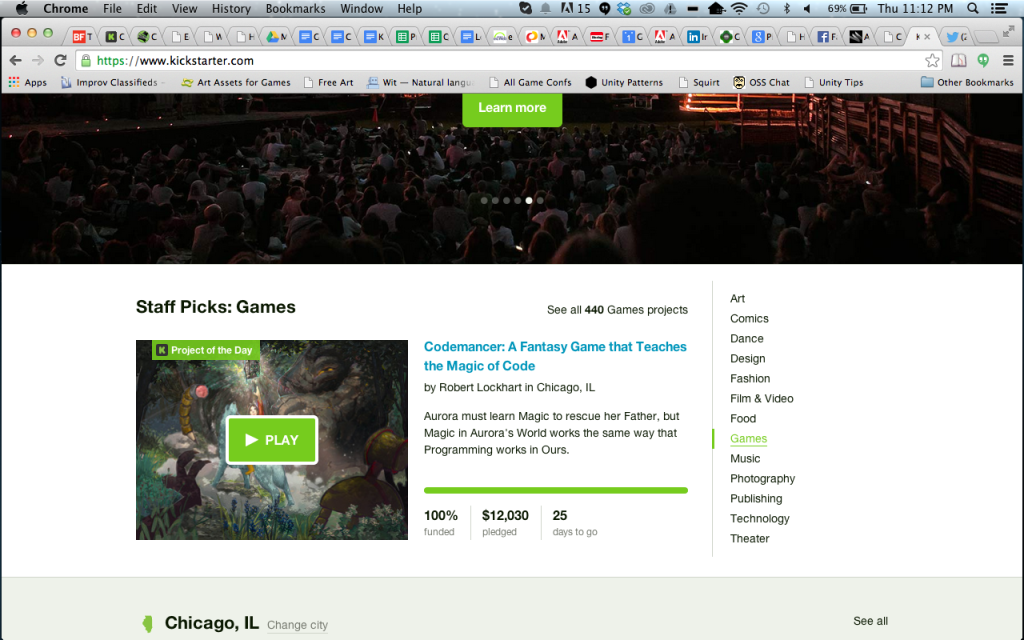

Project of the Day

Immediately after being funded, Codemancer was featured on the front page of kickstarter.com as the project of the day. I have no idea why, and I’ll probably never know. I reached out to a few people at Kickstarter, namely Cindy Au, who has some concentration on the games section of Kickstarter, and Fred Benenson who was an early employee of Kickstarter and a person who I met a few times when we were both taking computer science at NYU. Neither of these people responded to me directly, but maybe putting Codemancer on the front page was their way of responding?

In any case, you can see a huge spike in funding on day 5 because of being featured ($6,981 that day alone), and I think that momentum carried on even after a new project of the day was chosen.

Press

Reaching out to the press is something I wish I had done earlier and more often, but in all of my preparations for the Kickstarter, I realized that I wasn’t going to have time to do a proper job of it. Honestly, if any aspect had to go a little neglected, I’m glad it was the press (no offense, journalist friends!).

Despite the late notice, many sites covered the project anyway, and while I’m really happy to get the word out to everyone, I’m not certain how much press coverage translates into actual pledges (we’ll see a bit more about that in the next section).

One exception is BoingBoing, one of my favorite nerdy online ‘zines. I used their online submission form to suggest that Codemancer be covered (including full disclosure that I’m the creator of the project), and, amazingly, Cory Doctorow wrote up the campaign. The ‘BoingBoing Bump’ had a palpable affect on pledges and on the amount of twitter hype the game was getting. You can see the effect around Day 22 on the graph above.

I also self-posted on reddit, which gave birth to a fairly long thread, and led to an impressive number of pledges.

Breakdown of Backers

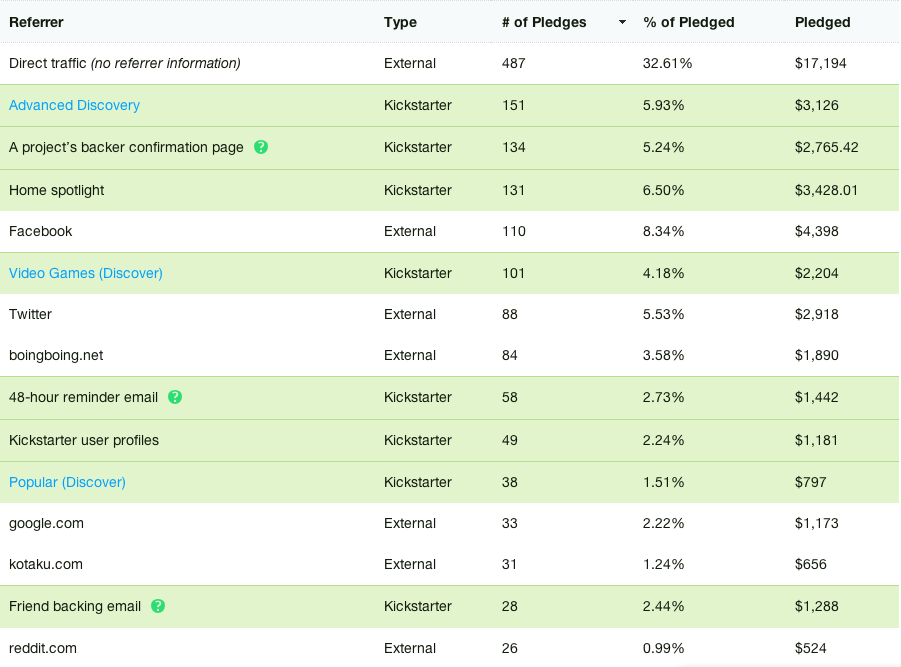

Where were these people coming from? Well, there’s a view on Kickstarter where project creators can see the referral information. Here it is sorted by number of people directed to the campaign:

There are more below, but each contributed 23 or fewer backers.

So what do these things mean? The first and most common source of backers was ‘Dunno.’ No idea where those folks came from. Next is ‘Advanced Discovery’ which means people on Kickstarter searching for certain parameters, like ‘Games made in Chicago with keyword Code’ or somesuch. The ‘backer confirmation page’ is the suggestions users are offered after backing another project, for example ‘backers of XYZ also backed Codemancer.’ The Home Spotlight is people coming from the front page when Codemancer was the project of the day. I think the rest of the sources are relatively self-explanatory.

I expected Facebook to rank above Twitter in terms of dollars pledged, since most of my friends and family were likely to hear about the campaign there first, but it surprises me that Facebook also ranks above Twitter in terms of number of backers. I’d love to hear if others have had similar results.

It’s also interesting to note where my backers come from geographically. With a short Python script, I was able to scrape that data from the Kickstarter site and put this map visualization together on CartoDB (with a little help from this batch geocoding service).

1,262 backers included their locations in their Kickstarter profiles, which is about 2/3 of all Codemancer backers. Chicago had the most backers, which isn’t surprising because that’s where I live. I have previously lived in Boston and New York, and they both made the top ten, as well. The full list is quite long, but the top 20 cities by number of backers were Chicago, San Francisco, Seattle, London, New York, Boston, Los Angeles, Melbourne, Austin, Washington DC, Sydney, San Jose, San Diego, Raleigh, Houston, Dallas, Minneapolis, Brooklyn (Kickstarter counts this as its own city, for some reason) and Toronto.

There were also many backers who reached out to me during the campaign about localization. Some even offered to help with the translation themselves. The requested languages were German (5 requests), French (2), and Spanish (1), Japanese (1) and Hungarian (1). I can’t guarantee I’ll be able to handle all of these requests, but I’ll certainly try. In any case, it’s great to get a sense of who wants this sort of game most.

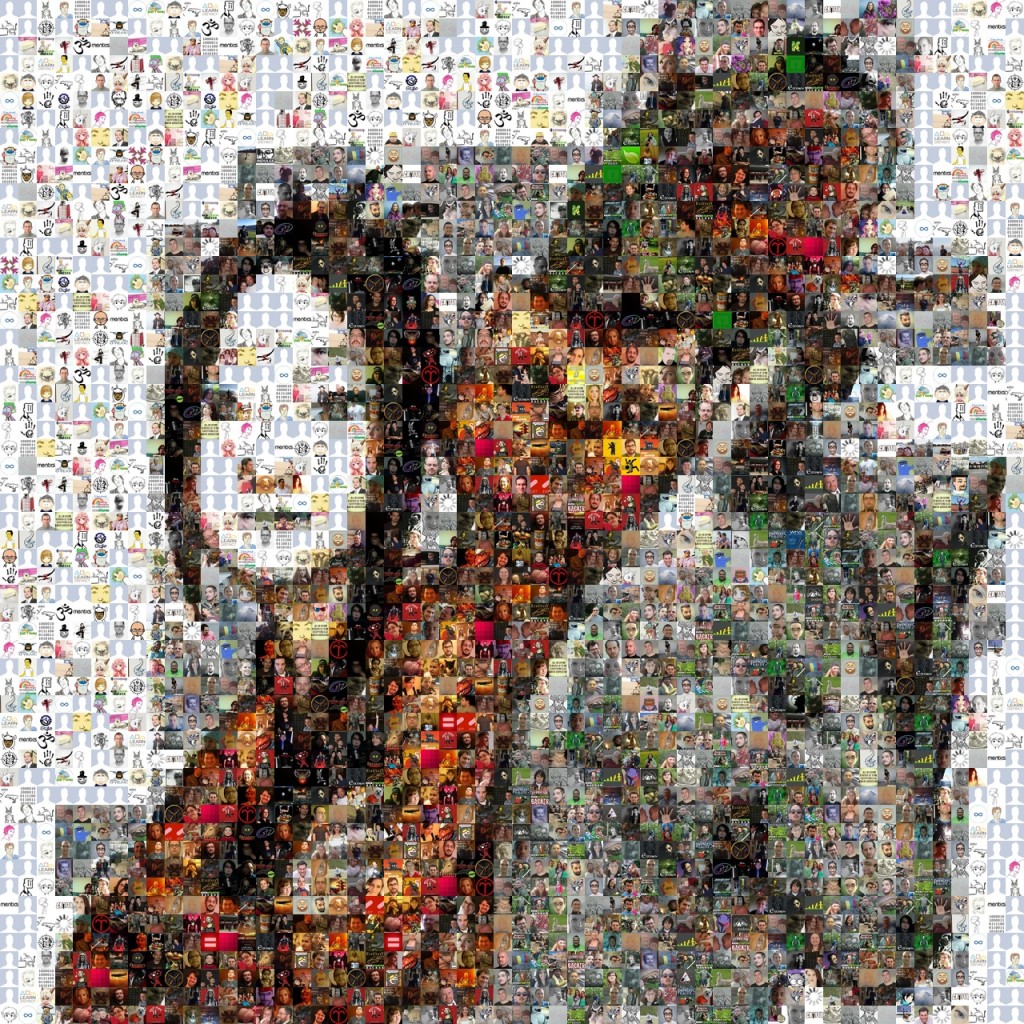

And in case you want to see what all of the backers (who have Kickstarter avatars) look like, here they all are!

Breakdown of Finances

Lastly, let’s look at the various ways that $52,725 is not the actual amount of money I can use to continue to develop Codemancer:

- Pledges that didn’t go through. I didn’t have as much of a problem with this step as many other folks that I’ve talked to. $52518.43 actually made it to Kickstarter, which is 99.6% of what was pledged.

- Kickstarter’s fee. They take 5%, or in my case $2625.92, leaving $49,892.51

- Credit processing Fees. This percentage differs depending on the credit card used, so I was never sure how much this was going to end up being. Now I can tell you it amounted to $2,151.66 or about 4.3%, which leaves $47,740.85

- Taxes. I’ve been advised to put away 20% of that amount for income tax in the US (which may be conservative).

That said, the remaining $38,192.68 is a perfect amount of money to see Codemancer through the rest of development, even after fulfillment (thank goodness I didn’t offer any physical rewards) and stretch goals.

Conclusion

I’d definitely recommend Kickstarter to others, assuming you start preparing early and don’t have a full-time job. Even doing contracting during the campaign was difficult for me, and I brought on friend and PR expert Ryan Olsen to help me manage it all. I can’t recommend Ryan’s work highly enough, especially for a single-person company like Important Little Games.

That said, Kickstarter was incredibly valuable even beyond the funding, in that it gave me all kinds of information. I learned about how to explain my goals for Codemancer to different audiences. I know more about what kinds of people are interested in the project. I know more about their desires and hopes for the game, and more about my own as well.

Thanks again to everyone involved, and to all the people who gave me such great advice about the game. If you’d like to be involved, too, you can pre-order the game here.

~

I’m Rob Lockhart, the Creative Director of Important Little Games. If you were to follow me on twitter, I’d be grateful.